Scenario based strategising using Eidos

Background:

The scenario technique was pioneered by Shell in the ’70s. Since then, it has been used by large corporations and governments across the globe.

A strategy is ultimately about creativity (seeing the options) and synthesis (deciding on a superior course of action) and NOT about analysing data – Henry Mintzberg

The role of the scenario technique would be to boost the ability of top management to identify superior courses of action that are different from the status quo and to foresee the consequences.

Challenges in scenario-based strategizing

Fundamental problems: Traditional strategic planning exercises tend to follow formal rationality, with the tendency of managers to emphasize short-term, feedback-based learning rather than aiming to anticipate long-term events and their consequences.

Strategizing in uncertain environments has to build on strategic foresight- the ability to identify a superior course of action, which is different from the status quo, and foresee its consequences.

Procedural challenges: Decision-makers usually tend towards cognitive biases, which inevitably have potentially adverse effects. Scenario planning can help and has been attributed to a positive impact on decision quality compared to more traditional tools.

Scenario planning reduces different types of decision-related biases, such as confirmation bias and overconfidence.

When groups collaborate to make decisions, we also have to deal with (stochastic) bias and the general discussion bias that favours preference-consistent information. Additionally, vested self-interests of group members or dominant group leaders may prefer inferior alternatives.

From practical experience, transparent step-by-step and group-based evaluation procedures that require fact-based argumentation are means to control such behaviour.

Scenario-based decisions create “understanding of the interaction between the actions, goals and knowledge of the individual organisation and the environment in which they are operating” and can thus be expected to contribute to enhancing decision quality (Harries-2003).

Visualising discussion content in groups has a facilitation effect on the solution of hidden profiles (situations where the ‘correct’ choice is not available from the beginning).

It has been scientifically demonstrated that parallel information processing can compensate for cognitive limitations such as memory capacity or attention resources. The neuroscientific basis of the visual systems parallel processing mechanism was shown by Nassi and Calloway (2009).

Topological-geographical relations provided by diagrams (visualisations) are superior to verbal descriptions when it comes to problem-solving. Visual inspection of performances and spreads are most helpful in supporting decision-makers in MCDA (multi-criteria decision analysis).

It can be thus concluded that compelling visualisations should boost, in particular, the ease of judgement and transparency.

The Parmenides Matrix Approach

Introduction: When designing scenario-based strategizing approaches, we need to balance trade-offs and optimise criteria defining the strategizing quality. We propose a disaggregation and individual visualisation of the necessary reasoning process into its essential cognitive steps. The subsequent re-aggregation in a structured, transparent and accessible “reasoning architecture” allows the strategizing team to interactively rethink and base conclusions on shared assumptions, cause-effect relationships and priorities.

The situation analysis must be sufficiently systematic to ensure comprehensiveness of drivers and strategic objectives. The strategizing needs to include sufficient time and analytic depth to facilitate a creative and out-of-the-box dialogue among the strategists. Lastly, decision-making needs to be promoted in a way that ensures that the strategists can collaborate efficiently and acquire a feeling of ownership.

Process Sequence

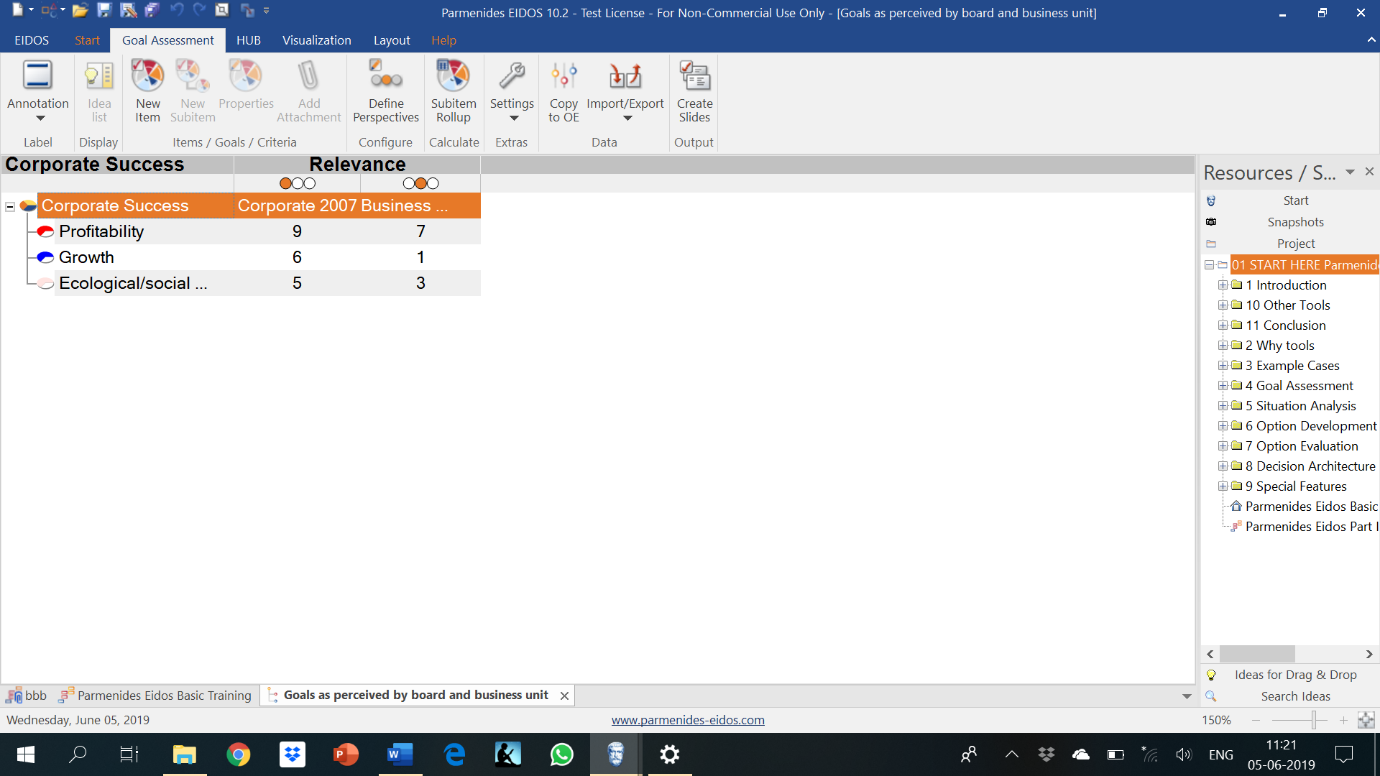

Step 1: Objectives/Goals

Goals are set, which must be specific enough to serve as evaluation criteria. They would be further prioritised by assigning weights. These weights and values can be expected to vary across the short, mid and long term. Eg. A firm may aim to grow aggressively in the short and mid-term, to eventually reach high profitability and high level of corporate sustainability in the long term.

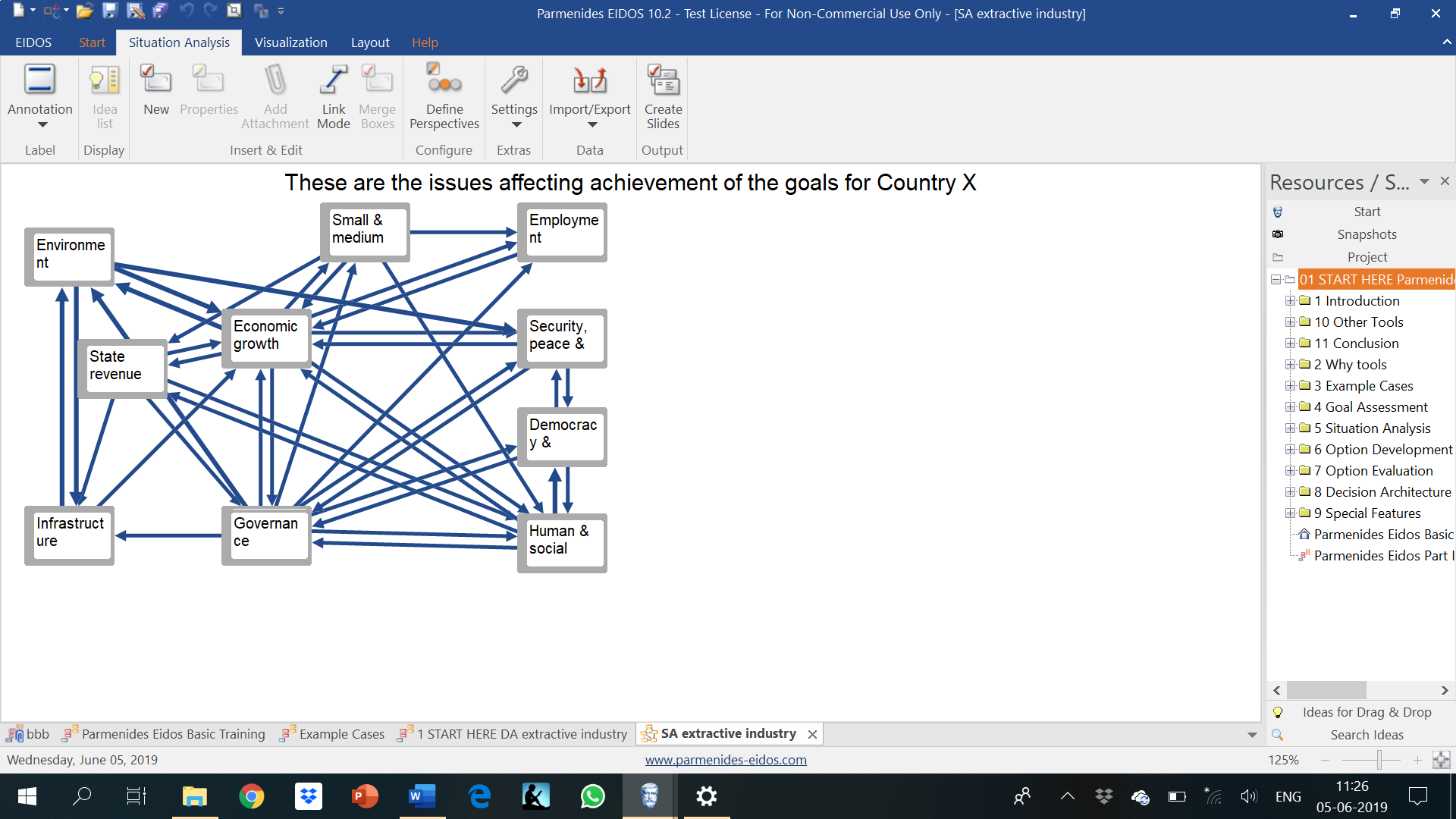

Step 2: Key Drivers

The aim of this step is to identify a set of change drivers. There are various processes like PESTLE or SWOT, which help in this. In the final step, key drivers are grouped into factors under our control (endogenous) and those beyond control (exogenous). The endogenous factors will be used as input for strategy development and the exogenous as input for developing scenarios.

Step 3: Scenarios

The key exogenous drivers form the basis for defining the scenarios. Scenarios should ideally reflect all of the residual uncertainty in the environment, i.e. cover the entire scope of plausible futures.

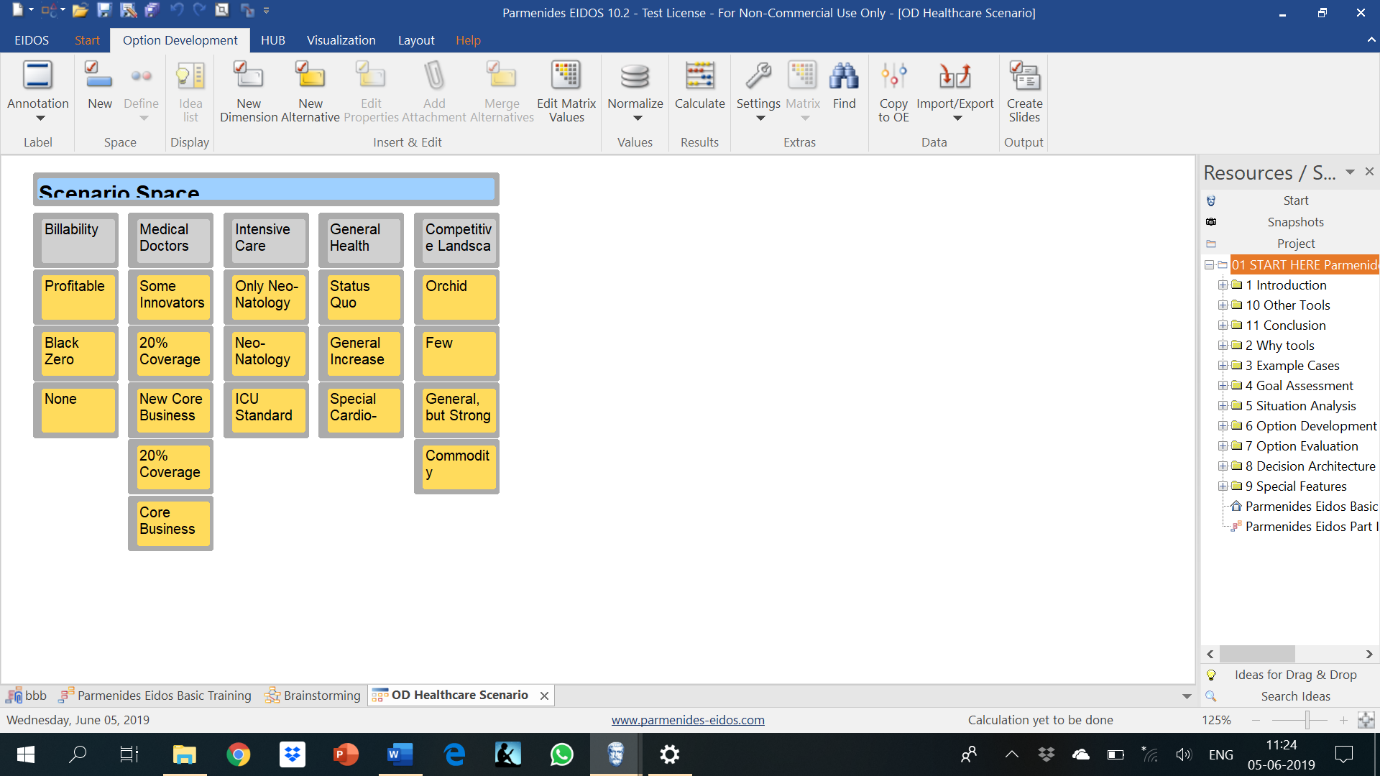

Step 4: Strategies

Independent construction of strategies is a key to challenge existing strategies, mental models and assumptions.

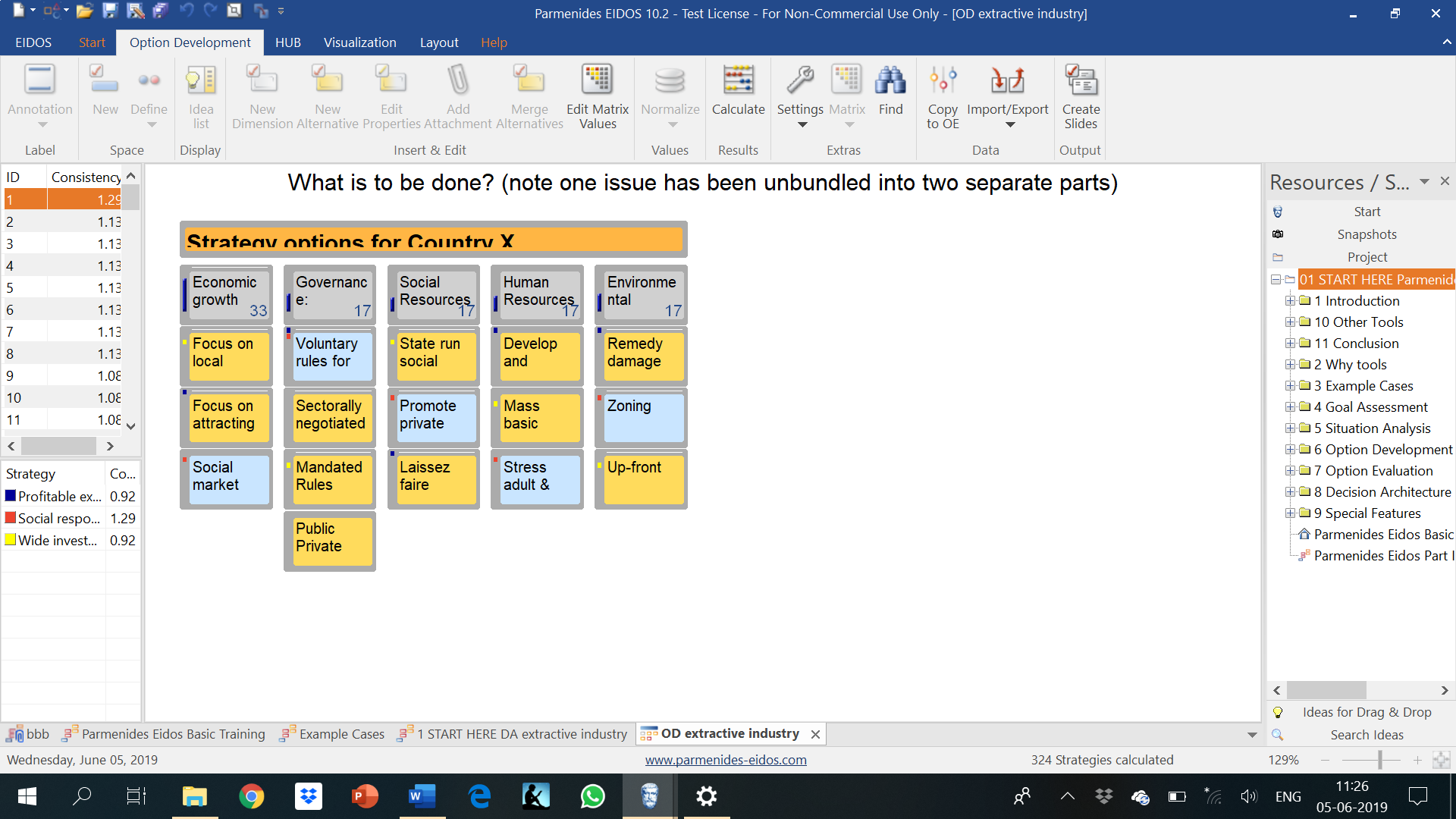

A useful method here is morphological analysis, which uses the endogenous key drivers as dimensions.

The construction of strategies as options, rather than as a variation of the existing strategy, allows the development of more distant strategies, i.e. strategies that deviate significantly from the status quo. The more distant the alternatives, the higher the likelihood of identifying a course of action that creates a competitive advantage

Step 5: Efficacy Evaluation

To identify an optimal strategy, decision making is broken down into two steps: efficacy evaluation and then robustness evaluation.

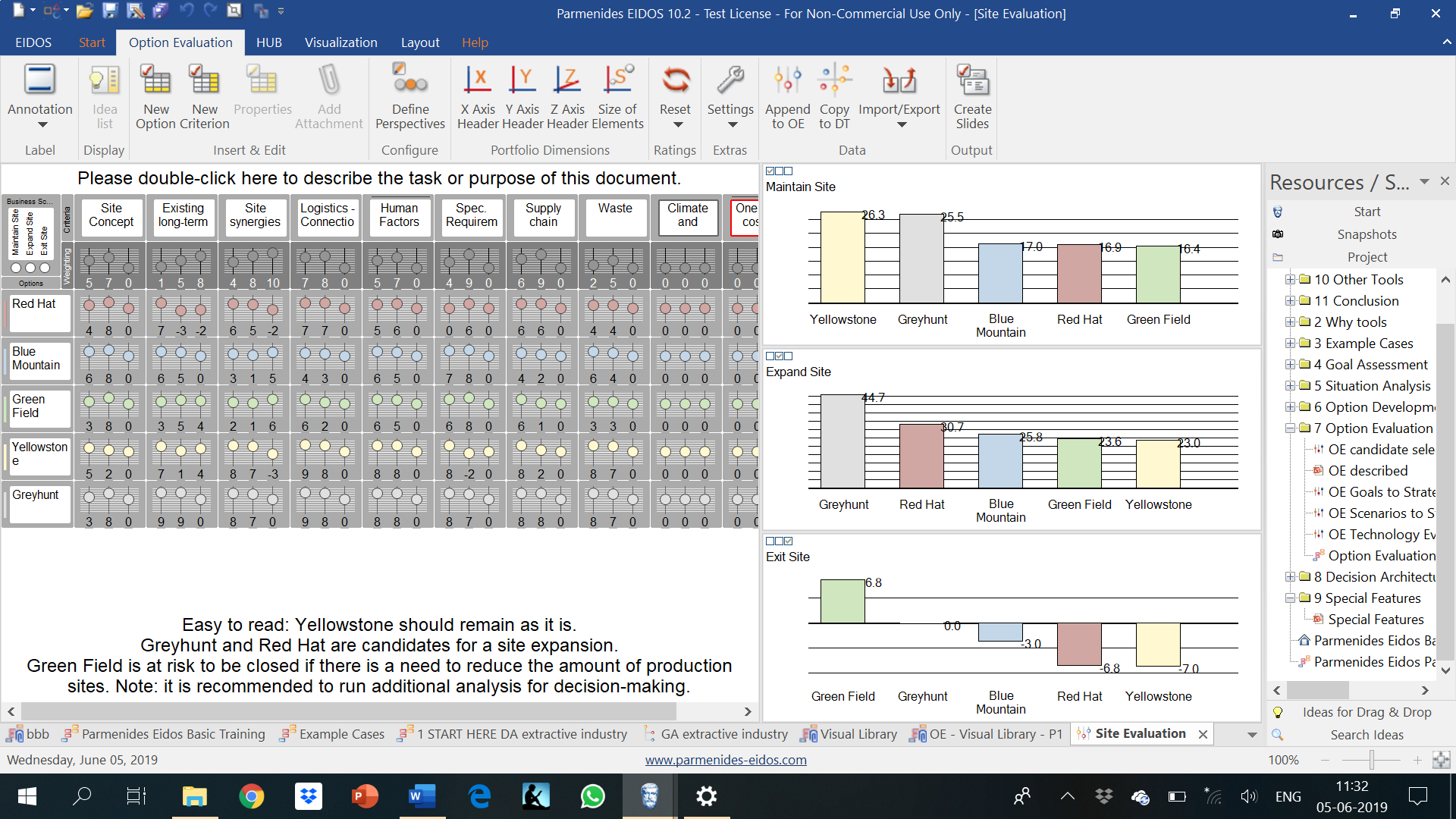

In the efficacy evaluation, the strategists are asked to evaluate to what extent the strategy supports the different goals defined in step 1. This step uncovers typically essential trade-offs. For example, one approach may boost revenues at the expense of profitability, while another one scores high on cash flow but low on revenue and profitability.

Step 6: Robustness

In this step, the strategists assess the robustness of the proposed strategies under different scenarios. Questions like “Which strategy is the best/worst adapted to a given scenario?” Criteria for evaluation can be feasibility, suitability and the acceptability in a given scenario.

Step 7: Parmenides Matrix

Once both the evaluations have been carried out, the results are plotted on the Parmenides Matrix.

The Parmenides Matrix also offers a platform for strategists to have an informed discussion about trade-offs and preferences to inform the final decision. Questions can include the following:

- How vulnerable is the most effective (goal-oriented) strategy?

- How effective is the least scenario-dependent (most robust) strategy?

- How effective are my strategies in a specific (maybe most probable) future scenario?

The Parmenides Matrix is the basis for identifying the optimal strategy. Plotting the analysis in a matrix enables the strategists to have a deeper level of discussion in which, frequently, assumptions about the risk preference of the organisation and the relative importance of objectives are challenged. It also permits a more in-depth validation of the analysis and, if necessary, altering the scores. We can thus expect that the usage of the Parmenides Matrix can boost both the ease of judgement and transparency.

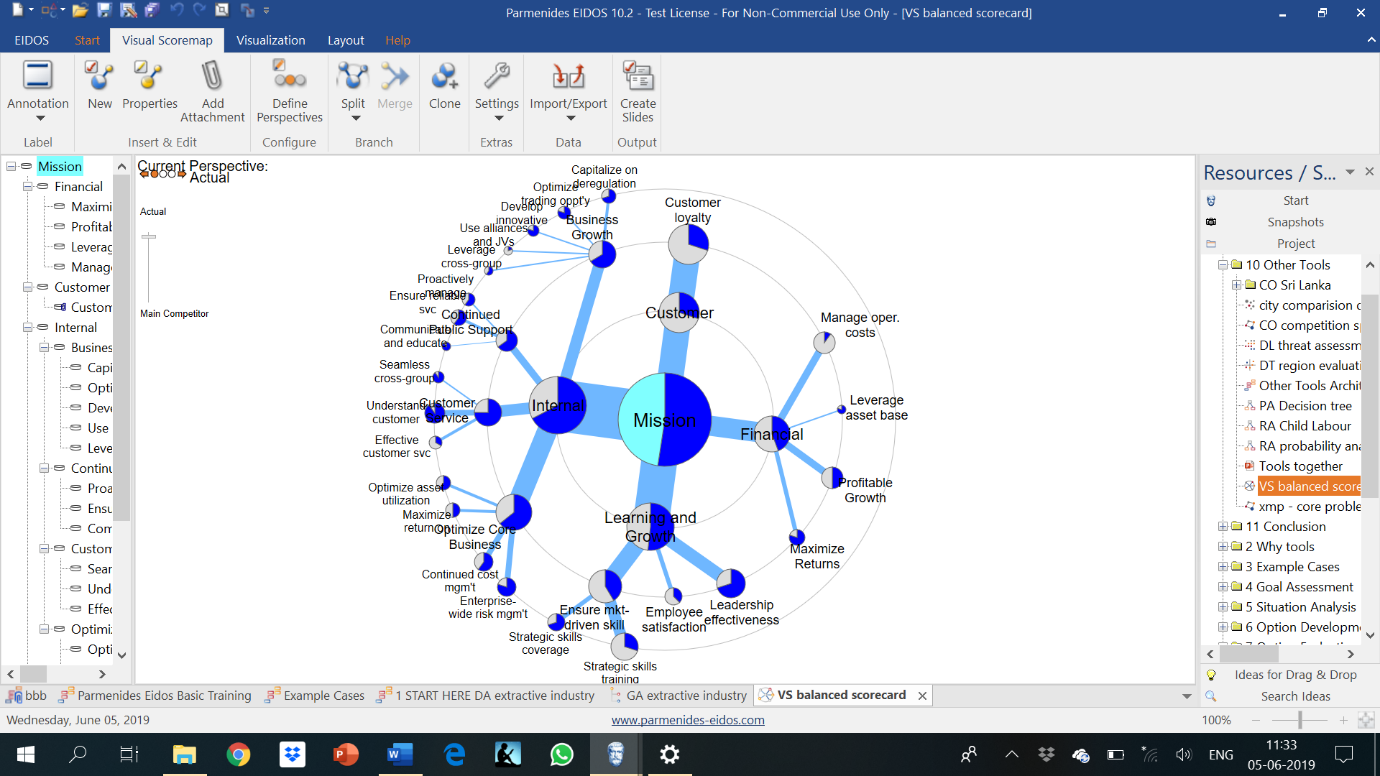

There are other potent tools like the Visual Scorecard, which is used to visualise and pinpoint specific elements in big data. They will be dealt with separately.